Reading List — The Story of Art Without Men

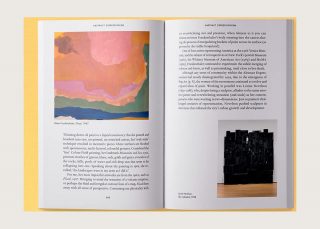

Katy Hessel is an art historian, broadcaster and curator who we first discovered via her Instagram and subsequent podcast The Great Women Artists. This September, Hessel launches her groundbreaking book, The Story of Art Without Men. Instead of female artists being seen as the muse of, or wife of, or model of Hessel places these women within their social and political contexts, and as such surfaces the unknown trailblazers of each significant movement in art history. We are delighted to share an extract of her poignant introduction that outlines the monumental void in our cultural history.

Throughout autumn, Hessel is presenting a series of talks and events across the UK. This Thursday there is an open to everyone signing at launch at Victoria Miro, alongside her curated show The Story of Art as it’s Still Being Written. On Thursday 15 September she will be in conversation with Charlie Porter at Daunt Books, and you can also listen to the extract below with her audio version here.

Introduction Written by Katy Hessel

In October 2015, I walked into an art fair and realised that, out of the thousands of artworks before me, not a single one was by a woman. This sparked a series of questions: could I name twenty women art- ists off the top of my head? Ten pre-1950? Any pre-1850? The an- swer was no. Had I essentially been looking at the history of art from a male perspective? The answer was yes.

At the time, the exclusion of women artists (and other under- represented figures) from the history of art was becoming an urgent issue. I had just graduated from my BA in Art History and had chosen to study Alice Neel (1900–1984, p. 346), a great American painter of psychologically charged portraits of people from all walks of life. But Neel was only recognised as a major painter by the art establishment when she was already in her seventies. Studying Neel helped me notice the overwhelming under-representation of women artists – they weren’t in galleries, they weren’t in museums, they weren’t in contemporary shows and they weren’t to be found in art history.

Why was this? The lack of women recognised as significant artists has been a subject of debate since at least the 1970s, when Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? was published at the dawn of the second-wave feminist movement. Over forty years later, it didn’t seem that enough had changed.

When listing the artists who are typically said to ‘define’ the art-historical canon, it is the following names that most often come up: Giotto, Botticelli, Titian, Leonardo, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, David, Delacroix, Manet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Kandinsky, Pollock, Freud, Hockney, Hirst.

I am sure that many of you will have heard of them. But how many of these artists would you recognise: Anguissola, Fontana, Sirani, Peeters, Gentileschi, Kauffman, Powers, Lewis, Macdonald Mackintosh, Valadon, Höch, Asawa, Krasner, Mendieta, Pindell, Himid? If I hadn’t actively studied women artists for the past seven years, I doubt I would know more than a fraction of these names.

Should any of this be surprising? Not according to statistics. A study published in 2019 found that in the collections of eighteen major US art museums, 87 per cent of artworks were by men, and 85 per cent by white artists. Currently, women artists make up just 1 per cent of London’s National Gallery collection. This same museum only staged their first ever major solo exhibition by a historic female artist, Artemisia Gentileschi, in 2020 (p. 35). And 2023 will mark the first time the Royal Academy of Arts in London has ever hosted a solo exhibition by a woman in their main space (Marina Abramovic ́, p. 310). Just one woman of colour has individually won the Turner Prize (Lubaina Himid, p. 393), in 2017, and it took until 2022 for the first women of colour to represent the US (Simone Leigh, p. 429) and the UK (Sonia Boyce, p. 396) at the Venice Biennale, the most prestigious art event in the world. When I conducted a YouGov survey in early 2022 to find out the British public’s knowledge of women artists, results showed that 30% could name no more than three (83% of 18–24-year-olds could name not even three), and more than half said they’d never been taught about women artists at school.

The night of the art fair I couldn’t sleep. Frustrated and angry about what I’d just witnessed, I typed the words ‘women artists’ into Instagram. Nothing appeared. And so, @thegreatwomenartists (a name that pays homage to Nochlin) was born. I set myself the task of writing daily posts spotlighting artists ranging from young graduates to Old Masters working across every medium, from painting to sculpture, photography to textiles. Adopting an accessible style, my aim was then, as it is now, to appeal to anyone of any art-historical level interested in learning the stories of these mostly overshadowed artists, just as I have done, on a more expansive scale, in a podcast of the same name which launched in 2019. I do this to break down the stigma around elitism in art – art can be for anyone, and anyone can be part of this conversation – and to showcase artists so often excluded from the history books and courses I studied. It’s not that I believe there to be anything inherently ‘different’ about work created by artists of any particular gender – it ’s more that society and its gatekeepers have always prioritised one group in history. And I think it is vital for this to be addressed and challenged. Nearly seven years later, the result is this book: The Story of Art without Men.

This is not a definitive history – it would be an impossible task – but I am looking to break down the canon I have so often been confronted by in the culture in which I have grown up. The canon of art history is global, however, with the male Western narrative being so unjustly dominant at the expense of others, it is this that I unpack and challenge. The book takes its title from the so-called introductory ‘bible’ to art history, E. H. Gombrich’s The Story of Art. It’s a wonderful book but for one flaw: his first edition (1950) included zero women artists and even the sixteenth edition includes only one. I hope this book will create a new guide, to supplement what we already know.

Artists pinpoint moments of history through a uniquely expres- sive medium and allow us to make sense of a time. If we aren’t seeing art by a wide range of people, we aren’t really seeing society, history or culture as a whole, and so I hope more books will follow this one, expanding the canon even more.

Progress is happening. This is thanks to a collective effort by actively engaged artists, art historians, scholars and curators around the world, all of different ages and backgrounds. It is their work I am greatly indebted to, as without them it would have been impossible to write this book. I draw here on the extensive research by (and my discussions with) spearheading art historians and curators who are endeavouring to change our understanding of art and who makes it, and you can find their works listed in the Bibliography at the end of the book. Many of them have uncovered the detail of these artists’ lives for the very first time. There is no denying that the increased attention to non-male artists enjoying blockbuster shows or appear- ing more frequently on museum walls is due to those who now hold top-tier positions in museums. For the first time in history, women have taken the helm of the Tate, the Louvre, and The National Gallery of Art, D.C., to name but a few.

What does this demonstrate? That the inequalities in galleries and museums are reflective of a larger systemic issue, and so a lot of what we see needs to change. The same can be said for how we place monetary value on genders in society, considering that the highest price fetched at auction by a living woman artist (Jenny Saville’s Propped, 1992) was just 12 per cent of the highest price achieved by a male living artist (David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972) which topped $90.3million. I hope this book will show you that the difference in price is not due to inherent quality, but to the value we put on different creators of art.

In the past decade we have seen a huge number of art-historical ‘corrections’ take place. From the numerous survey exhibitions dedicated to women sculptors, painters, abstractionists, or surrealists, such as Fantastic Women: Surreal Worlds from Meret Oppenheim to Frida Kahlo, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965– 1985, or Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, to the first major solo exhibitions of Pauline Boty (p. 268), Carmen Herrera (p. 290) and Hilma af Klint (p. 100), among others. I hope we will see more – and that my next art fair offers me a different experience to the one back in 2015.

So here is my take on the ‘story of art’ (without men). Because while the statistics remain so shocking, it feels important to remove the clamour of men in order to listen carefully to the significance of other artists to our cultural histories. Beginning in the 1500s and ending with those defining the 2020s, I have divided this book into five parts which each focus on significant shifts or moments in mostly Western art history. To avoid artists only being seen as the wife of, the muse of, the model of, or the acquaintance of, I have situated them within their social and political context, in the time in which they lived.

While I have grouped artists within established movements (for the purpose of clarity), I am keenly aware that artists are not the products of categories, but rather individuals with varied lives and careers who spearheaded key changes in styles. In the history of art, however, such moments have nearly always been attributed to men, and women’s pioneering work has been overlooked. So, although I have merely skimmed the surface of many of these artists’ multi- layered (and for some, still evolving) oeuvres – which can encompass more mediums, cultures, styles or time spans than those works and movements discussed here, I hope this book will give you an insight into at least a fraction of the work of non-male artists who have contributed to the ‘story of art’.

Related Content

A Moment With Charlotte Perriand

Jun-2021If Le Corbusier is a giant of modernism, Charlotte Perriand—the woman he collaborated with, and who co-designed some of the furniture that featured in his ‘machine for living in’—is less well-known, and often uncredited. Plus ça change.

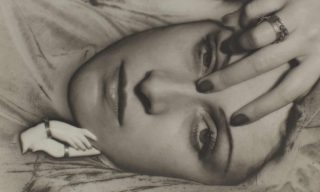

A Moment With Dora Maar

Feb-2020Well known as the model for Picasso's 1937 work The Weeping Woman, it transpires that Marr was an impressive creative in her own right. In the final month of the her major exhibition at the Tate Modern, we present six points to intrigue.

Patter Places — Holidaying as an Art Lover

Sep-2021As holidaying becomes a possible pursuit for many in the coming months, we recommend three European cultural destinations that offer it all — sun, good food, nature and contemporary art.